16 Fascinating Historical Artifacts Stored In The Library of Congress

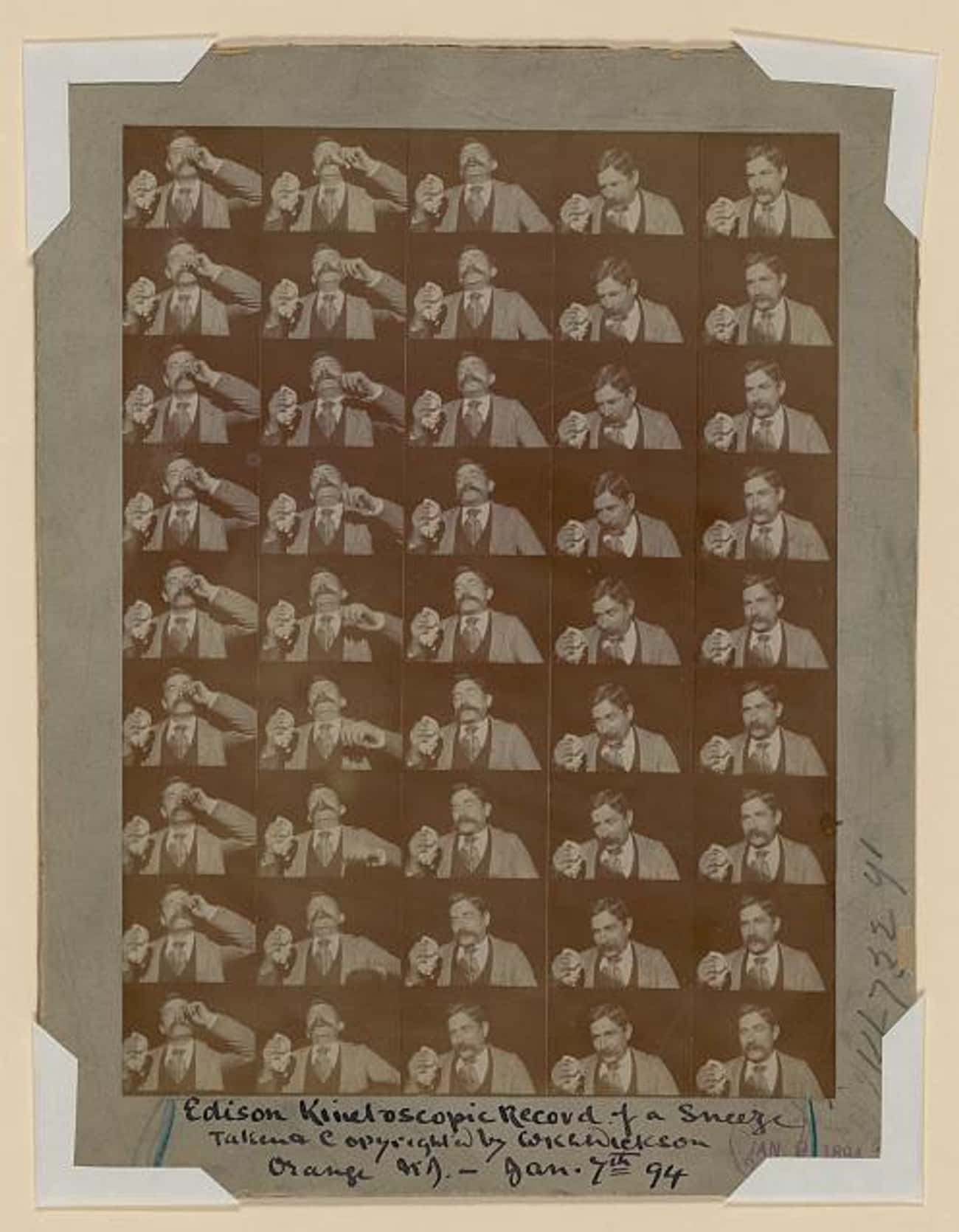

Fred Ott's Sneeze

Photo: W.K.L. Dickson / Library of Congress / Public Domain“Ah-CHOO.” Sneeze and you’ll miss this five-second movie, the first motion picture to be copyrighted in the United States. Fred Ott's Sneeze is a black-and-white, silent kinetoscopic film shot in 1894 by William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson, one of Thomas Edison’s assistants. In the film, Fred Ott, an Edison employee known for his comic antics, takes a pinch of snuff and sneezes. According to the Library of Congress, it was filmed "for publicity purposes as a series of still photographs to accompany an article in Harper’s weekly.”

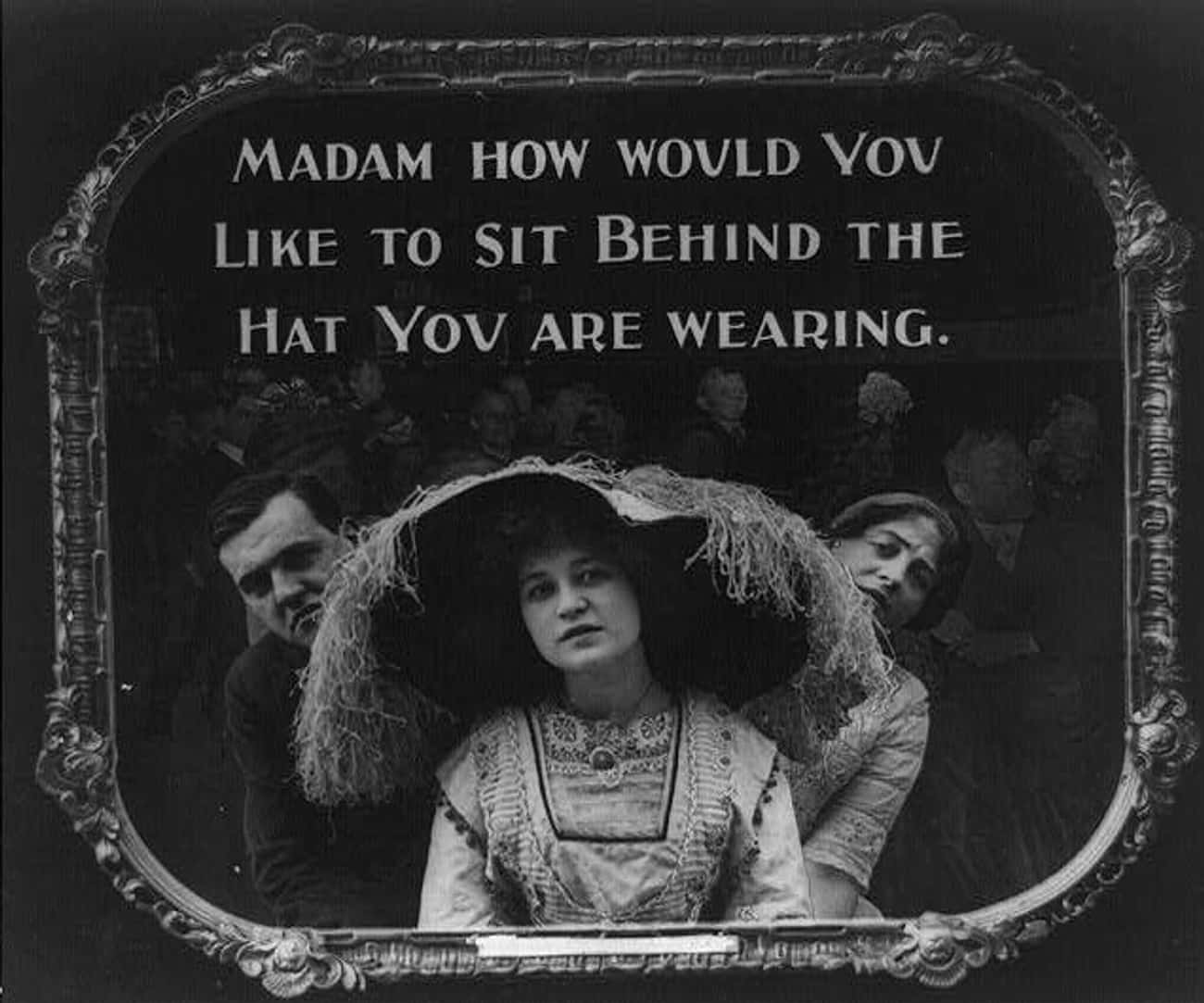

Movie Etiquette Slides

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public DomainModern-day movie theater annoyances that necessitate pre-film and on-screen warnings generally refer to turning off cell phones. In the early days of cinema, the big offenders were less technical but equally obtrusive: ladies’ hats. The Library of Congress has a collection of slides from old movie theaters in the early 1900s with “movie etiquette” suggestions like “Applaud with hands only” and “If annoyed when here please tell the management.” Or, for women with towering headgear, “Madam how would you like to sit behind the hat you’re wearing.”

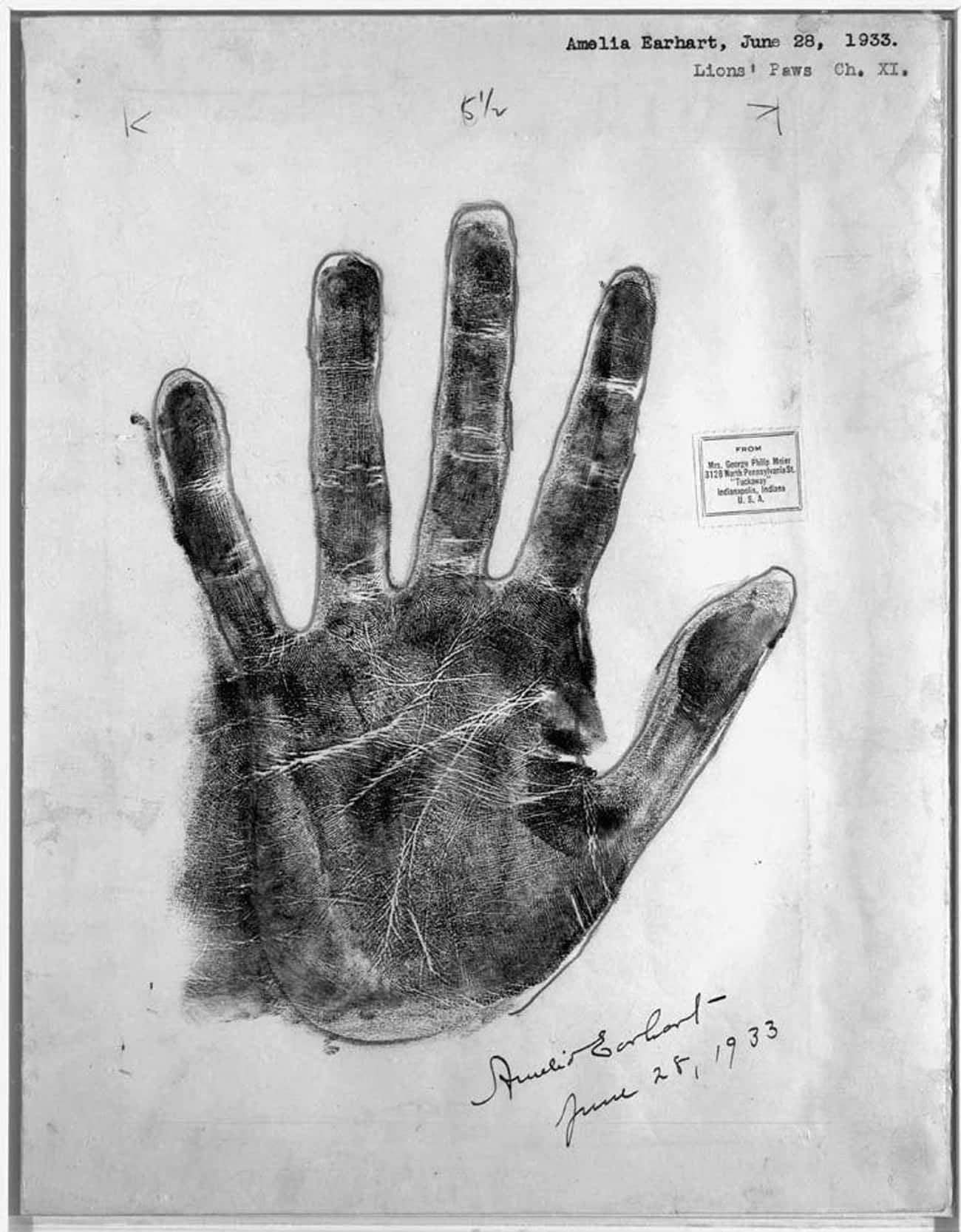

Amelia Earhart's Palm Print

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public DomainPalmistry is the practice of studying someone’s hands as a way to interpret the person’s personality. Palmist Nellie Simmons Meier examined the hand prints of famed aviator Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, in 1933 – four years before Earhart mysteriously disappeared during a flight over the Pacific Ocean. In Meier's book Lions’ Paws: The Story of Famous Hands (the book’s original prints and character analyses were donated to the Library of Congress), she wrote the following about Earheart:

The length of the palm indicates the love of physical activity, but the restraining influence shown by the length of the fingers, indicative of carefulness in detail, enables her to make careful preparation toward accomplishing a definite goal.

America's Birth Certificate

Photo: Waldseemüller, Martin / Library of Congress / Public DomainThe “birth certificate” is actually a world map described as the first document printed with the name “America.” Created by cartographer Martin Waldseemüller in 1507 CE and acquired by the Library of Congress in 2003, the world map has a mouthful of a Latin name: “Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii aliorū que lustratione,” which translates to “A drawing of the whole earth following the tradition of Ptolemy and the travels of Amerigo Vespucci and others.” To Americans today, the map probably looks fairly accurate, but to long-ago Europeans, “America” was a big chunk of unknown continent. The document is also the first map to show a separate Western Hemisphere and Pacific Ocean.

A Monopoly Board Game Precursor

Photo: Parker Brothers / Library of Congress / Public DomainBefore Parker Brothers started selling the popular game Monopoly in 1935, the company dabbled in economics and business via a board game called “The Office Boy,” released in 1889. According to the Museum of Play, the game was produced during the days of Horatio Alger’s stories about young men achieving the American Dream. Players work their way up in the company from stock boy to traveling salesman to junior partner to head of the firm. “Carelessness” and “temperance” set players back; “integrity” and “promptness” put them on the path to promotion. The Office Girls didn't even get to pass Go.

Locks Of Famous People's Hair

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public Domain"Shining, gleaming, streaming, flaxen, waxen... hair." Well, not so much anymore. These locks have lost their luster, but the Library of Congress does have samples of hair from famous people, including Thomas Jefferson, Walt Whitman and James Madison. Jefferson's family took the cuttings from his deathbed. Whitman's housekeeper chopped off a few strands of his hair. Madison's clippings are tidily braided inside a velvet-lined gold case.

Bizarre Health Product Labels

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public DomainWeight watchers in the U.S. at the turn of the century were more worried about being too thin (unhealthy) than being too fat (a sign of vim and vigor). This color lithograph from the Library of Congress, published circa 1895, is an advertising label for fat-producing products called Loring's Fat-Ten-U food tablets and Loring's Corpula food. A drugstore ad for the products, complete with skinny before and corpulent after drawings, said they were “guaranteed to make the thin plump and rosy with honest fleshiness of form."

'Red Hot Democratic Campaign Songs For 1888'

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public DomainToday, politicians get in trouble for using popular songs during their campaigns that haven’t been approved for that purpose by the artist. Solution: self-penned campaign ditties, like “The Other Candidate," part of a book of sheet music called Red Hot Democratic Campaign Songs for 1888 at the Library of Congress. The song (for “male voices”) starts out “You may cheer for the grand old party, / As you cheered in the years before, / But her prestige has all departed, / And shorn are her pride and power.” Oh, and the word “eighteen eighty-eight” is in the song, too; it rhymes with “candidate.”

The Contents Of Abe Lincoln's Pockets When He Died

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public DomainAbraham Lincoln was honest, honorable, and one of our most esteemed presidents, but he was also an ordinary guy. When Lincoln was assassinated in Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865, his pockets were full of everyday items: two pairs of glasses, a six-blade pocketknife, a quartz-and-gold watch fob, a linen handkerchief with “A. Lincoln” stitched in red, newspaper clippings, and a leather wallet – with, of all things, a $5 Confederate note inside. These artifacts, given to Lincoln’s family after his death, first went on display at the Library of Congress in 1976 to "humanize" the former president.

The First Road Map/Guide Book Of The U.S.

Photo: Christopher Colles / Library of Congress / Public DomainBefore geography jumped into our phones and GPS systems, travelers relied on printed maps. Someone, of course, had to map out the maps. Christopher Colles was one such person. The engineer-surveyor-cartographer created what is considered the first road map of the U.S., A Survey of the Roads of the United States of America, published in 1789 (the year George Washington became president). Each page contains maps that cover a somewhat short distance, making navigation easier and more detailed than perusing a larger map.

George Washington's Rules Of Civility

Photo: George Washington / Library of Congress / Public DomainAs a schoolboy, George Washington hand copied 110 Rules of Civility & Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation. This lengthy code of conduct was based on rules compiled for young men by Jesuits in the 16th century. The rules cover everything from manners to morality. Some are a bit outdated, such as No. 9: “Spit not in the Fire, nor Stoop low before it neither Put your Hands into the Flames to warm them, nor Set your Feet upon the Fire especially if there be meat before it.”

Others are timeless, even if the language is a little stuffy, as in No. 100: “Cleanse not your teeth with the table cloth napkin, fork, or knife; but if others do it, let it be done without a peep to them.” And we can all heed No. 110: “Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.”

Culinary Advice For Motorists

Photo: Harper & Brothers / Library of Congress / Public DomainToday, on a car trip to just about anywhere in the U.S., finding nourishment is easy, with a fast-food outlet, liquor store, or protein bar close at hand. In the early days of auto travel, however, the “motor picknicker or camper” in May Southworth’s The Motorist’s Luncheon Book (1923) had trouble finding eateries, so on-the-road culinary prowess was key. Some of the items on Southworth's list of suggested emergency food supplies might turn modern-day stomachs, though: beef tablets, sardines, canned frankfurters, “bacon in jars,” and pancake flour. The book also contains gourmet on-the-go recipes like Sausage Surprise and Salad Suzette (served with cream of pea soup in paper cups).

Thomas Jefferson's Vanilla Ice Cream Recipe

Photo: Thomas Jefferson / Library of Congress / Public DomainThe Library of Congress contains the largest collection of Thomas Jefferson documents in the world – more than 27,000 items that showcase his skills as a diplomat, politician, writer, scientist, architect, and historian. But this favorite Founding Father was also a dessert maker. His highly detailed recipe for vanilla ice cream – also available in his papers at the Library of Congress – is super natural. The ingredients are simply “good cream,” egg yolks, sugar, and vanilla. For a more decipherable version of the recipe, visit The Kitchn.

A Fire Insurance Map That Shows The O.K. Corral

Photo: EDR Sanborn / Library of Congress / Public DomainSo many western films have dramatized the famed gunfight at the O.K. Corral that it’s easy to forget the battle was real. The 30-second skirmish between the Earps and Clanton-McLaury gang took place Oct. 26, 1881, in Tombstone, Arizona. The Library of Congress, in its extensive collection of maps, has an 1886 fire insurance map (used back then by insurance underwriters) that shows the location of the O.K. Corral, in block No. 17, on Allen Street between Third and Fourth streets. The gunfight actually took place in a vacant lot behind and to the west of the corral.

First Known Book Printed In America

Photo: Unknown / Library of Congress / Public DomainOfficially – but clunkily – titled The Whole booke of Psalmes faithfully translated into English metre, North America’s first known printed book is also called The Bay Psalm Book because it was created in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1640 (20 years after the Mayflower landed). Basically, it’s a hymnal, with words but no music notes. It’s translated from Hebrew to English, with funky old spellings: “With expectation for the Lord / I wayted patiently, / and hee inclined unto mee, / alfo he heard my cry.”

Helen Keller's Plea To Alexander Bell

Photo: Helen Keller / Library of Congress / Public DomainIn the early 1900s, famous folks, like everyone else, communicated via telegram. The celebrities involved in a 1907 telegram donated to the Library of Congress are Helen Keller, who was deaf and blind, yet became a noted speaker and activist, and Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone and was also an advocate for deaf people. In the telegram, sent before Keller delivers a talk in New York, she asks Bell if he will “stand beside me and repeat my speech so that all may hear?”